November 27, 2005

Cece's Later Life

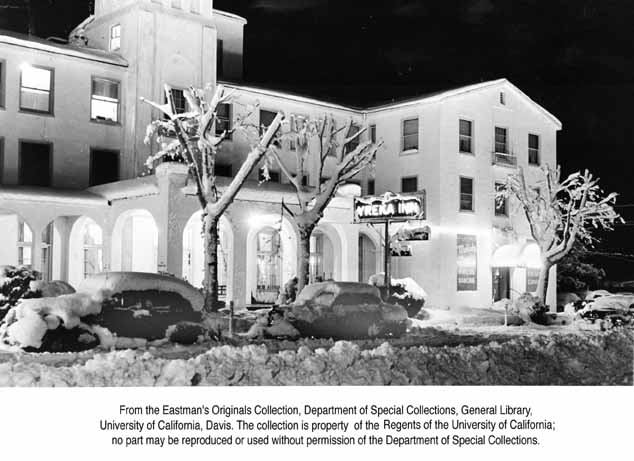

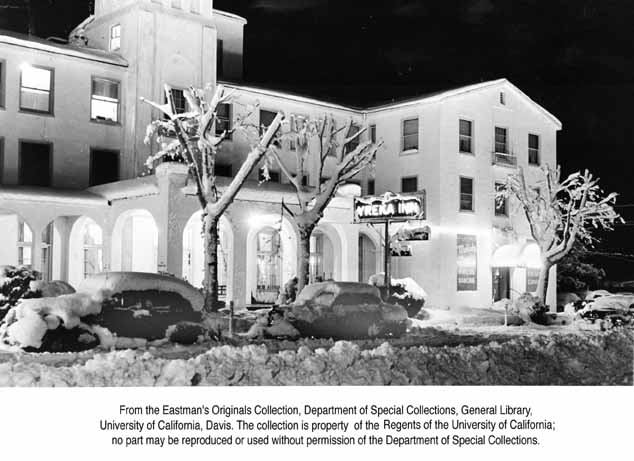

Cece later met and married George Stack, who owned Stack’s Bank Club in Alameda, California. After the war, George sold the Bank Club and purchased the Yreka Inn, a luxury hotel, in Yreka, California. Cece and George mutually operated this hotel until they eventually sold it and purchased a motel in Yreka. They eventually divorced. [George was having personal problems and, shortly afterward, he took his life.]

Yreka Inn, Snowbound, 1950

Cece went to work at the Navy Officer’s Club at the Naval Air Station in Alameda. She then purchased Rosie’s Diner, in Alameda, which she operated for several years. Ray Hinckley, who had been manager of the officers club when she worked there, came to the diner to work as her manager. They later married. After some difficulty, probably a difference in managerial philosophy, they divorced.

Cece and Ray Hinckley (Click for a Larger View)

Albert Brixius, a Coast Guard Chief, completed his time [in the Service], retired and came to help Cece run the diner. They later married and remained married until Cece’s death in 1979. She died of cancer at the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, California on October 25, 1979.

Al Brixius, Early 1960s (Click for a Larger View)

Cece was a generous person who helped numerous people through the years.

--John Crowley

Yreka Inn, Snowbound, 1950

Cece went to work at the Navy Officer’s Club at the Naval Air Station in Alameda. She then purchased Rosie’s Diner, in Alameda, which she operated for several years. Ray Hinckley, who had been manager of the officers club when she worked there, came to the diner to work as her manager. They later married. After some difficulty, probably a difference in managerial philosophy, they divorced.

Cece and Ray Hinckley (Click for a Larger View)

Albert Brixius, a Coast Guard Chief, completed his time [in the Service], retired and came to help Cece run the diner. They later married and remained married until Cece’s death in 1979. She died of cancer at the Oak Knoll Naval Hospital in Oakland, California on October 25, 1979.

Al Brixius, Early 1960s (Click for a Larger View)

Cece was a generous person who helped numerous people through the years.

--John Crowley

November 25, 2005

Marriage and Child

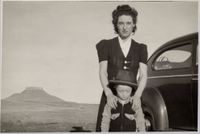

Cece & Tommy at Thunder Butte (Click for a Larger View)

Cece used to go to the country dances with my brothers Joe and Neal. They watched over her and she enjoyed a good time. When she was about eighteen, Cece met Ted Dickinson at one of these country dances. He came to the ranch for a long time to see her. They went to the dances in the area and enjoyed a nice courtship. They were married by the Catholic priest at the Catholic Church in Lemmon. Ted was not Catholic, so it was not the formal church wedding. I remember the ceremony quite well because I was one of the people who stood for them.

With her new husband, Cece set up housekeeping in Lemmon. After the first year, their child was born—a boy they named Thomas Elting Dickinson. The “Thomas” was for her [and my] father and “Elting” for Ted’s father. Soon Tommy, Cece’s baby, was found to have Down’s syndrome. It used to be called “mongolism” because the child’s features were thought to be Mongol in appearance. We all loved the little boy. But the father, Ted, was demoralized. To make things worse Cece was unable to have another child. Their marriage deteriorated from this point on, for the next year or so, until they finally divorced.

When her marriage failed, Cece took a job waitressing at Gordon’s Cafe, a large restaurant on Main Street in Lemmon. My mother moved to Lemmon, rented an apartment upstairs over the Golden Rule Store, and took care of Tommy, the baby, while Cece worked. I also worked at Gordon’s [while attending high school in Lemmon], scrubbing floors, bussing dishes, washing dishes, and even helping Gordon with the preparation of meals. Things remained uneventful for the remainder of the school year, until my mother moved back to the ranch, where she was needed.

I am not clear on the rest of Cece’s life in Lemmon. But, when we entered World War II, Cece and little Tommy came to California with my brother, Joe, and my mother. During WWII, Cece worked as a waitress at the Alameda Hotel Restaurant. Her little boy, Tommy, died during the war while Cece was working and my mother was caring for him. The doctor said his heart literally burst. I think he was five years old when he died in Alameda. It must have been in 1943.

--John Crowley

November 23, 2005

No Place for a Girl to Grow Up

Cecelia Crowley as a Teen, Probably About 1930 (Click for a Larger View)

Cecilia Cynthia Crowley was born February 6, 1915 at the family homestead west of Thunder Butte. Cece, as she was called by nearly everyone who knew her, was about nine years of age when I first remember her. And, I do remember her very well because I was like her kid, doll, toy, or whatever term fit the situation. She assumed the responsibility of caring for me when I was too young to care for myself, and it does seem to come natural to little girls to watch over their younger siblings.

Cece was slight of build, as I first remember her, with long blonde curls. Her hair later turned to a dark brown. She had big blue eyes, set wide apart and, although slight of build, she was very wiry, holding her own with all of the wild people and creatures of the South Dakota landscape.

When I began the first grade in school, at the age of six, I was accompanied to school by Cece, on our horses. She was then ten. Soon after, before the year had well begun, Cece quit school. The long ride in the cold and the country kids with their snotty noses were just too much for her.

When Cece was about twelve or thirteen years old, she went to live with our Aunt Cynthia in Lake Williams, North Dakota. Lake Williams is almost in the center of the state of North Dakota. It is on the shore of a beautiful lake where the estate of James J. Hill is located. Mr. Hill started the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific railroad.

Cynthia Shockley Gulden was my mother’s sister. She had married well, as they used to say. Her husband, Lee Gulden was a partner in Gulden Brothers and Faulk, which had lumber yards, farm implement stores and real estate. At one time they owned many thousands of acres of North Dakota farm land which they put out on shares to local farmers. Cynthia kept in close communication with my mother.

About this time there were three basic types of guys on the South Dakota plains, cowboys, coyotes and sheepherders. As my mother and Cynthia saw it, this was no place for a sweet, beautiful young girl to grow into womanhood. She began grade school in Lake Williams and apparently finished there. After grade school she went to a Beautician’s school in Jamestown, North Dakota, and later a "charm school” in the same town. These later became modeling schools and agencies.

From time to time, Cece would come home to the ranch. For summer vacation and other special occasions. One of these times, when she was about fifteen and we were living on Thunder Butte Creek, we suffered an experience which colored my life. I was sent out, as usual, just before dark one day to round up the milk cows and bring them in for the night’s milking. The system of finding the cows was to ride up on a high hill, sit quietly on the horse and listen for the cow-bell which would sound out as the cows threw their heads about while eating and swatting insects. If you didn’t hear the bell, you rode on to other hills and repeated the process.

This particular night, as it grew dark, I could not find the cows and eventually had to go home and confess failure. Cece said, "I’ll go get them,” and she set off on horseback to complete the job that I had failed at. Long after dark—she had been gone for about two hours—Cece came home on foot and told the following story.

She had ridden in to a place where there had been a wire fence. There were piles of old barbed wire on the ground, but she and the horse were unable to see the wire until the horse had become entangled in it. He got excited and thrashed about in the wire. She got off to try untangling him when he jerked her into the wire and entangled her in the wire, as well. I remember my mother removing Cece’s clothing to treat her lacerations. Her chest, stomach and shoulders were severely lacerated and she was covered with blood. Of course I was the butt of some pretty severe criticism, because Cece was out there trying to find the cows and it had been my job to find them. Well, I guess you know how I felt.

--John Crowley

November 03, 2005

The Difficult 1930's

South Dakota was stricken hard by drought during the 1930’s. Harold Breimyer, in his book, “Over-fulfilled Expectations: a Life and an Era in Rural America,” recounts doing survey work in Ziebach County in 1938. According to Breimyer, “Ziebach County in 1938 was barren. Only a handful of homesteaders was still to be found.” Among them were the Crowleys, who had settled near Thunder Butte in 1913.

Breimyer says, “They [the homesteaders] had taken up their 160 acres before World War I. A few years of good crops and wartime high prices had offered a false hope that was extinguished with all the tragedy that James Michener describes in Centennial.” Michener’s book, “Centennial,” is a tribute to the West and all of the dramatic hopes and conflicts spurred by generations of fur trappers, cowboys, homesteaders, ranchers, and gold seekers.

In many ways, Ziebach County and the area around Thunder Butte were typical of the West that Michener described. French fur trappers passed through the country beginning in the 1650’s, to be followed by successive waves of Americans seeking their fortune as explorers, ranchers, and homesteaders in the dry lands of the West.

During the 1930’s, according to Breimyer, “South Dakota may have suffered more than any of the (then) forty-eight states from depression and dust-storm drought.” Often, when people think of the 1930’s droughts and the migrations they caused, they think of the poor sod farmers from Oklahoma who picked up and moved west. Few people probably know that while Oklahoma lost 2.5 percent of its population during the 1930’s—almost 60,000 people—according to T.H. Watkins, writing in “The Hungry Years,” South Dakota lost seven percent of its inhabitants, and just short of 50,000 people. Ziebach County was among the hardest hit areas—losing almost 30 percent of its population during the 1930’s. These numbers understate, though, the masses of people—300,000 to 400,000 according to some estimates—from around the country who were on the move, looking for jobs, better land, or a new place to put down roots.

Soon after 1940, most of the Crowleys gave up the toil of ranch life near Thunder Butte and moved to California. Tom Crowley stayed behind for awhile, until his wife and the rest of the family had gotten settled in the San Francisco Bay Area. Only Neal Crowley remained and prospered for years afterward in the town of Faith, not very distant from the family’s former home.

Breimyer says, “They [the homesteaders] had taken up their 160 acres before World War I. A few years of good crops and wartime high prices had offered a false hope that was extinguished with all the tragedy that James Michener describes in Centennial.” Michener’s book, “Centennial,” is a tribute to the West and all of the dramatic hopes and conflicts spurred by generations of fur trappers, cowboys, homesteaders, ranchers, and gold seekers.

In many ways, Ziebach County and the area around Thunder Butte were typical of the West that Michener described. French fur trappers passed through the country beginning in the 1650’s, to be followed by successive waves of Americans seeking their fortune as explorers, ranchers, and homesteaders in the dry lands of the West.

During the 1930’s, according to Breimyer, “South Dakota may have suffered more than any of the (then) forty-eight states from depression and dust-storm drought.” Often, when people think of the 1930’s droughts and the migrations they caused, they think of the poor sod farmers from Oklahoma who picked up and moved west. Few people probably know that while Oklahoma lost 2.5 percent of its population during the 1930’s—almost 60,000 people—according to T.H. Watkins, writing in “The Hungry Years,” South Dakota lost seven percent of its inhabitants, and just short of 50,000 people. Ziebach County was among the hardest hit areas—losing almost 30 percent of its population during the 1930’s. These numbers understate, though, the masses of people—300,000 to 400,000 according to some estimates—from around the country who were on the move, looking for jobs, better land, or a new place to put down roots.

Soon after 1940, most of the Crowleys gave up the toil of ranch life near Thunder Butte and moved to California. Tom Crowley stayed behind for awhile, until his wife and the rest of the family had gotten settled in the San Francisco Bay Area. Only Neal Crowley remained and prospered for years afterward in the town of Faith, not very distant from the family’s former home.